Writing 101: Dramatic Structure

Hello all once again! Your favourite alien Limax, Vivian, is doing once again a quick and short introduction. My beloved friend Anne Winchell is doing yet again a guest post on Dramatic Structure! Lady Verbosa is at it again! She is still suffering from Lightpox but is making a recovery, how are you doing Anne? (Vivian out)

Important Anne Health Update

As you may recall from the symptoms of Lightpox, my lightbreath has progressed… Vivian, you can’t see the light from my eyes and hands, can you?

(Vivian: Nope! Worst part is that if you want them gone, you cannot tell them to walk into the light. They will just hit a mirror then.)

Oh yeah, NOW you tell me! 🙄 I guess it is what it is… it’s just so darn itchy! I’ll try to keep focused… I’ve been drinking tea nonstop and hiding in darkness, so it’s only a matter of time, right? Okay, Anne, engage your focus on dramatic structure! Aaaand… go! Warp speed sounds playing

What is Dramatic Structure?

Picture the story that you want to tell. What do you imagine? Interesting characters? A new world or galaxy? An interesting plot, or maybe a conflict? All of these are cogs in the machinery of a story. Vivian does a great job explaining the concept of cogs and describing different types in zhir post Worldbuilding 101: Cogs, but essentially all of these are different elements that combine to make your world. In worldbuilding, there’s little need for these cogs to be structured causally to create meaning, but when you’re writing or creating, it’s absolutely vital. We as creators combine these cogs in unique ways to create our stories, but what shapes our stories and melds the cogs together is the dramatic structure.

Throughout this post, I’m generally going to refer to written stories and novels. However, be aware that this applies to all storytelling! Other written forms like poetry and plays easily fit in, but so do things like music and video games. I actually teach a college class on dramatic structure in video games! They’re interesting because they’re nonlinear, but the same basics apply. Anything that tells a story has a dramatic structure, and all can be understood based on the structures described below.

When most people think of stories, they think of the classical beginning, middle, and end. Now, in terms of chronology, this isn’t always the case. The movie Memento notably tells the story backwards in chunks! However, despite the events taking place in reverse chronological order, the dramatic structure is unchanged. Memento has a beginning, middle, and end, based on rising tension and conflict. However, this isn’t the only way to do a story.

Dramatic structure is based in the culture of a society, and different societies value different things. Does your culture value peaceful self-reflection? You might come up with kishōtenketsu, popular in East Asia. Does it value conflict as a means of advancement and believe that history is constantly improving and advancing over time? Ding ding ding! That’s the beginning, middle, and end structure driven by rising tension and shaped by conflict! Can you guess which culture this is? Yup, Western culture. And that’s the primary culture reflected in published stories around the world.

Regardless of what structure you choose, every story has the same essential purpose: to engage the reader. You want your reader glued to the page, your viewer skipping past commercials, binging the next episode, or talking about it with their friends if they have to wait a week to continue. You want gamers hooked, and listeners hanging on every word. No matter what story it is, no matter what structure, engagement is key. And for Western stories, this all hinges on the dramatic question. (Vivian: All this drama, and no llamas)

The Dramatic Question

Ah, the dramatic question… are you picturing someone on one knee proposing? Or maybe a significant other asking, “Do you love me?” Or, if you’re not into the romantic elements, a similar situation with a life or death situation where one person extends their hand and asks, “Do you trust me?” Those are certainly dramatic, and they are questions! However, that’s definitely not the dramatic question in stories! Hmm, I probably shouldn’t have even mentioned them, now you’ll get the wrong idea…

Stories told in the Western tradition have a dramatic question that guides them, but it’s not the questions described above. It’s usually a yes/no question that is answered in the climax of the story. It’s often fairly simple (will X get the girl? Will Y destroy the ring?) but it dictates the overall conflict. Each story generally has one central dramatic question that’s pretty easy to predict based on the genre of the story, but it gets broken down into smaller questions throughout the story. For example, when talking about if X gets the girl, there are a lot of steps that have to be taken before that’s even an option! Will the girl notice X? Will X be able to impress the girl? Will the girl forgive X for their mistake/betrayal? And when X does get down on their knee to propose, will the girl accept? So many steps! If your final answer is a yes, you want to have some nos along the way, and an overall no answer should have some yeses. The little victories and failures are important to add variety and tension, but they all build to that central question. (Vivian: Wherefore art thou llama?)

Gosh darn it, this lightpox is just so itchy! I can… just barely… reach it… I’d better drink some more tea… Okay, that’s better… On from the central question in general to more specific genres!

See, some genres have certain questions associated with them, and some genres have required answers. For example, romance almost always has a dramatic question along the lines of “Will the couple get together?” To be considered romance, which requires an ending that is either HEA (happily ever after) or HFN (happily for now), the answer needs to be some variant of “yes” (“yes, but” works for HFN). In tragedies, the answer is often “no.” There’s plenty of room between “yes” and “no,” of course! You can end on a “maybe” cliffhanger, or go with a mixed “yes in some ways, no in others.” Grimdark, for example, is often “yes, but at what cost?” Genre expectations are extremely important, so know your genre. And don’t feel limited to a binary!

If you’re writing a standalone novel, you’ll focus on a single dramatic question. If you’re writing a series, however, you have two: every individual book within the series needs its own unique dramatic question, and the series overall also needs a unique dramatic question. When writing books in a series for most genres, you don’t want to have a bunch of books with the same dramatic question, or they’ll feel repetitive. Try to mix it up!

Wait, Anne, you might be saying, what about Sherlock Holmes? Those stories all have the same dramatic question! Excellent point, I would respond, and it once again brings up the importance of genre. If you’re writing detective fiction, the dramatic question is almost always “Will X solve the case/catch the criminal?” Trying to do something different would be extremely unwelcome to readers and violate genre expectations. In this case, you absolutely should repeat your overall dramatic question.

When you have a serialized story like this, where each individual book or episode stands alone but also links together on a broader level, the rules are a little different. Think of most television or streaming series. As the great Phillip J. Fry once said, “TV audiences don't want anything original. They wanna see the same thing they've seen a thousand times before” (Futurama). There’s definitely some truth to this. Every episode accomplishes essentially the same thing (aka answers the same dramatic question). In Law and Order, a new crime is investigated and prosecuted. In the Great British Bakeoff, a dwindling number of bakers face baking challenges.

The major question in each episode is the same, but the smaller questions that build up to that bigger question are different, giving each episode uniqueness and keeping us interested. Get too formulaic, and you’ll lose your audience! You want to keep enough of it the same that it has the distinctive “feel” of your story, but different enough that it isn’t repetitive. You want to combine the feel of seeing the same thing you’ve seen a thousand times before with originality so that they want to keep watching or reading new stories. You get the same three types of challenges in Great British Bakeoff, but each week has a different theme, and you never know who is going to succeed and who is going to fail (answering the dramatic question “who will become star baker?”, a good example of one that isn’t yes/no).

It’s good to know what your central dramatic question is so that you can build your story around it, but some writers don’t figure it out until they’ve reached the answer and realize everything up to this point has been leading to it. It depends on your writing style, but at some point, you need to identify your dramatic question and the little questions leading up to it to ensure that your story remains cohesive. (Vivian: Dramatic question of this post, in which section will you find the llama emoji?)

The All-Encompassing 3 Act Structure

You’ve probably heard of other dramatic structures in Western literature, and you’re wondering why this one is so important. Well, it’s because every other structure is some variation of the 3 Act Structure! Vivian calls me a 3 Act Supremist, and I have to admit that it’s true. (Vivian: everyone, grab the pitchforks and torches!) When looking at Western literature or writing something for a Western audience, everything you write should adhere to the concept of the 3 Act Structure or some variant.

Basic 3 Act Structure

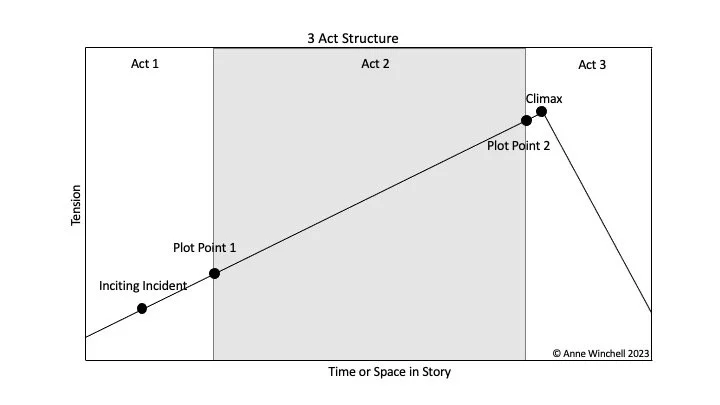

So if I’m a 3 Act Supremacist, the 3 Act Structure must be my favorite, right? Surprisingly, no. I like some of the more complicated structures we’ll look at below. But the 3 Act Structure is essential in understanding how virtually all of Western literature is laid out. The basic structure follows a beginning, middle, and end format, and it is defined by conflict. Events are connected by causality (though not always told in order), leading to a building of tension until the climax and resolution. There are several accepted points along the path, and some variations as well. This is the format prized by screenwriters, and you can chart many movies and TV shows to the minute based on this structure.

The following graph is going to be the basis of all of the other graphs and shows the basic structure that (almost) all Western stories use, with tension as the y-axis and time or space in the story as the x-axis. However, there’s one important note on this graph, and all of the graphs. I’ve drawn them as straight lines, but each story has ups and downs throughout, depending on the story. I’ve chosen to use straight lines to represent the overall arc, and also because the ups and downs are different in every single story. So as you look at this and the later graphs, please imagine lots of ups and downs, but all fairly close to the straight lines. The overall pattern holds true even if it’s not entirely accurate.

Act 1

Once upon a time… Back when tigers used to smoke… Beyond nine seas, beyond nine lagoons… A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away… All of these openings have been used around the world and in popular media to open up a world and welcome us in. They lay the scene quickly, evoking time and place, culture and genre. While you might not be able to achieve those things as quickly as those well-known phrases, Act 1 is basically expanding on that initial introduction to the setting, the characters, and their relationships to each other and to the world around them.

After setting the stage for your story, the next thing that happens is an inciting incident, or something that sets your story in motion. This is the introduction to conflict, which will be the driving force of the story. From this point on, the tension will only keep rising until the climax. So we now have a conflict, a situation, a problem of some sort: what are the characters going to do? Their first attempt to address this conflict becomes the first plot point and forever changes things for the characters. After this, they can never go back to their ordinary existence. The dramatic question is established, and the first act comes to a close. In film, Act 1 takes 30 minutes. (Vivian: A wild llama appears.)

Act 2

The story is really taking off now! Stakes continue to rise and the tension grows. The characters keep trying to address the problem introduced at the first plot point, and keep failing in various ways (or succeeding! Yay! And then finding out that there’s so much more to do). Even as you work towards an answer to the central dramatic question, your story will deal with all sorts of minor questions, some leading into side plots, some adding character development or depth to the world, but all eventually leading back to that main question. The majority of the story takes place in this act, and right when things are at their darkest and everything seems lost, we hit the second plot point. The answer to the dramatic question seems to be in danger! Is there any hope? This marks the shift into Act 3. In film, Act 2 takes 60 minutes. (Vivian: The llama keeps following along.)

Act 3

From the dark night of the soul that ends Act 2, we arrive at the peak of tension in the story: the climax. During the climax, the central dramatic question must be finally and definitively answered, no matter what that answer is. Once the tension has peaked, it begins to fall away in the denouement. The plot and all of the subplots need to be wrapped up, and a new status quo sets in. Often, characters have a new sense of self, relationships have been altered, or the world is changed in some way. Depending on genre, this might be negative or positive, and the new status quo may be permanent, or only last until the next book or episode.

If this is a standalone book, Act 3 should leave the reader feeling satisfied (though not necessarily happy depending on genre). If it’s in a series, you want to answer the dramatic question of the individual book, but leave the dramatic question of the series unanswered. You might also leave elements of the plot or subplots unresolved. However, it is VITAL that the book’s individual dramatic question be answered or else readers will feel cheated. In film, Act 3 takes 30 minutes. (Vivian: The llama is slain.)

The 4 Act Structure

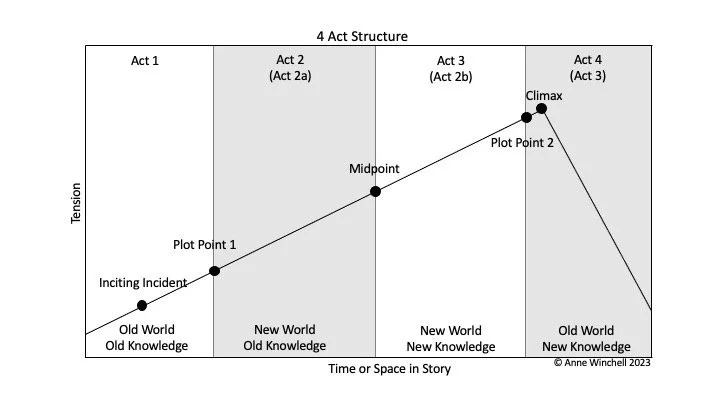

Okay, so the 3 Act Structure wasn’t my favorite–this must be it! Well, this one is definitely the one I use most often! I find it very practical, and I think it’s more useful than the basic structure we just saw. It has two ways of naming the parts, so I’ve provided both. Essentially, it’s the 3 Act Structure with the second act broken in half, which to me is extremely logical. Because of this, though, many people still refer to it as 3 Act Structure and just give Act 2 two names.

One reason that I like this structure better is that it separates out two key characteristics in the story: the world in which the story is set, and the knowledge that the characters have. I’ll expand on that in the description of each act.

Here’s a graph of this structure, and you can easily see how it improves upon the 3 Act Structure (in my opinion). It certainly makes it easier to talk about!

Act 1

Well, it’s the start of another adventure! And this act, well, is basically exactly the same as before. Same setup, inciting incident, and first plot point. However, looking at the world and knowledge aspects of the story, we can see why I like this structure a lot more. This act takes place in the old world, because it’s only after the first plot point that the character can’t go back. Everything before that point–in other words, this entire act–is in the old world. Sometimes the “old world” represents a physical setting, but it can also just be a mindset. It’s just something essential to the story that exists in Act 1, and then the first plot point irrevocably puts it out of reach. In terms of knowledge, we’re also operating with old knowledge. The characters are working from their starting point and haven’t really learned anything yet. Knowledge includes knowledge of the world, of the other characters, of the enemies, of the conflict… At this point, the characters are simply existing at their status quo in terms of knowledge. Once we hit that first plot point, we’re ready to dive into…

Act 2 (or Act 2a)

Boom! We’re in a new world! Everything has changed, and our characters can’t go back. We’re not in Kansas anymore! Now, here’s where we see the difference from the 3 Act Structure. Act 2 contains everything leading up to the midpoint. I didn’t mention the midpoint in the 3 Act Structure because it’s not always referenced as part of the structure, but it’s always there. Like the 3 Act Structure, Act 2 has rising action as characters try and fail (or temporarily succeed) to address the main conflict. We also get side plots at this point, and all sorts of other things.

The key difference, and the one that I think shouldn’t be ignored, is the role of the world and knowledge. We’re definitely in the old world, but what about knowledge? Well, in this act, characters are still operating with old knowledge. They’re trying to solve problems with the knowledge and ways of thinking and acting that have gotten them through life so far. The midpoint that ends this act and moves into the next is when characters gain new knowledge. Most commonly, they realize how to defeat the enemy (though it’ll take a lot of work to do it). They finally have a plan instead of just making isolated attempts! Or they might discover that who they thought was their enemy is actually an ally against a far darker threat. Maybe they master a skill, or at least learn that they need to master it. Basically, at the end of this act, the characters gain a sense of how to answer the dramatic question as they shift from the old knowledge of this act into the new knowledge of the next one. That midpoint is absolutely crucial, and it’s why I prefer this structure over the basic 3 Act Structure.

Act 3 (or Act 2b)

All right, we’re in the new world, and we finally have new knowledge! Time to save the world, right? Not exactly. Just because our characters have a plan now doesn’t make it any easier. Tension continues to rise. Conflict deepens. Those little steps towards the dramatic question get harder and harder, and things get worse and worse. This act ends with the characters at their lowest, when everything seems like it’s going to fail…

Act 4 (or Act 3)

Another climax! This is basically identical to the 3 Act Structure, but then it shifts in terms of world and knowledge. The characters maintain their new knowledge, but return to the old world. Sometimes this is literal, with characters literally returning home. Sometimes this is simply a return to a status quo, even if it’s a different status quo than they began with. Basically, they’ve returned to a previous state but preserved their hard-earned knowledge, so they now operate in a different way. As with the 3 Act Structure, this needs to answer the dramatic question and resolve conflicts.

The Sequence Structure

Okay, give me a minute here… I just need another cup of tea… I’m feeling a little dizzy, Shake it off, Anne. You know these dramatic structures like the back of your hand! Wait, is that a light lesion on the back of my hand? 😱

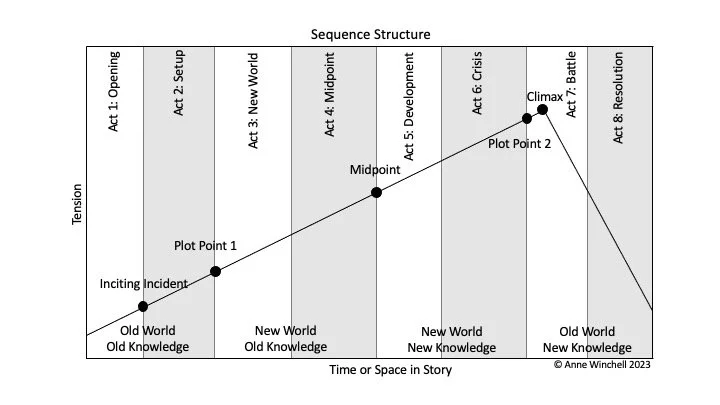

Um, so, uh, ignoring that… On to the Sequence Structure! While this structure isn’t often taught in classes, it’s valued in various media circles. It expands on both the 3 Act and the 4 Act Structure, breaking it down and adding specifics to what should happen when. Everything that I’ve said above applies, so I won’t repeat anything, just add the details that occur in this structure. As you can see, this is basically a detailed 4 Act Structure! This is really good if you need a little more structure and direction than the previous structures.

Act 1: Opening

This is pretty basic! It’s just establishing descriptions of the world and characters. This ends with the inciting incident.

Act 2: Setup

Still pretty basic. After the inciting incident, the characters start planning or acting or doing something to address the conflict. This ends with the first plot point.

Act 3: New World

See how well this lines up with the 4 Act Structure? This act is just an introduction to the new world as the characters adapt and learn.

Act 4: Midpoint

This scene encompasses the midpoint discussed above when the characters have a realization or gain new knowledge.

Act 5: Development

Not an especially exciting name for the act, I know, but that’s pretty much it. The story develops!

Act 6: Crisis

This is the lowest moment, when everything seems lost. Some stories spend a lot of time here, but some make it brief and poignant.

Act 7: Battle

While not necessarily a physical battle against a 🦙, this is the climax as the ultimate conflict is resolved.

Act 8: Resolution

As the name suggests, this is where all of the loose ends get tied up (unless you’re writing a series, in which you can leave a few threads dangling). Yet another story complete!

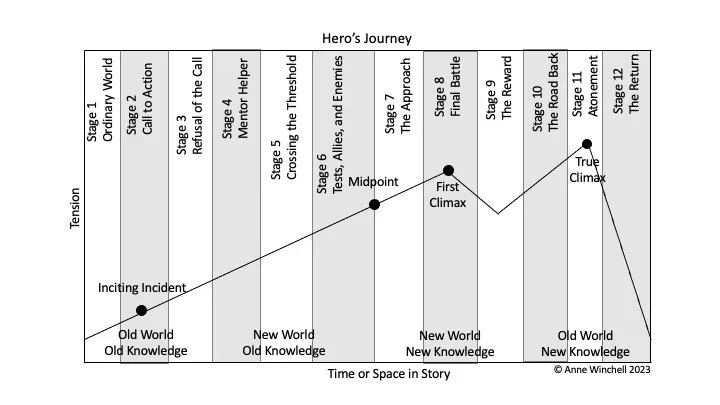

The Hero’s Journey

Ah, my favorite! Finally! There are a lot of variations of this structure, but I’ll be going with a version that has 12 stages. This is the one popularized in a memo by Christopher Vogler from 1985 that brought the Hero’s Journey, originally described in Joseph Cambell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, back to popularity. Just be aware that some versions get even more detailed! Do note that although Cambell labeled this structure, it’s been around for as long as we have records of storytelling! In addition, the labels of these stages are not always consistent between versions. However, this version is the heart of the Hero’s Journey, and you can use it as a good guide.

The Hero’s Journey has been written about extensively, and it’s also known as the Monomyth because it forms the core of so many stories. It’s the “one myth” that drives much of Western literature. If you have a book with a single protagonist, chances are good that you’re going to end up with something very similar to this even if you’re not trying. Even stories with multiple characters often follow this! The Hero’s Journey outlines the essential journey of a protagonist used in virtually all Western literature.

One thing to note is that this is still just an extension of the 3 Act Structure, with just a couple of slight adjustments to the climax and pacing! As I said, that 3 Act Structure is mighty useful!

Stage 1: Ordinary World

Ah, home sweet home! This scene is often brief and just sets up the status quo or starting world. Now, that doesn’t mean it’s peaceful! But it’s a stable existence of some sort, and it’s important to introduce the ordinary world to the readers so that they know what the hero is fighting for. After all, if the hero isn’t trying to preserve something or fight for something, can there really be good motivation? (...well, yes, but not in this structure!)

Stage 2: Call to Action

What’s this? Something has disturbed our stable existence! This is the inciting incident. Something happens to spur the hero to action. Surprisingly, it doesn’t actually need to be related to the main conflict! This just needs to get the hero up and moving out of their status quo, but they should stumble across the real conflict soon.

Stage 3: Refusal of the Call

I cannot overemphasize how important this step is. There MUST be pushback against the call to action. This forms the first plot point, and it’s when the hero either refuses to answer the call and is forced into action, or the hero attempts to answer the call but something prevents them. Maybe they decide not to go help a princess, but when they return home, their aunt and uncle are barbequed! (Star Wars: A New Hope) Now they have no option but to leave! As I said, this correlates to the first plot point, and once it happens, there’s no going back. New world, here we come!

Stage 4: Mentor Helper

This is a bit of an odd stage in that it can actually happen at other points, but it usually happens here. All stories have a mentor of some sort who guides the hero. That doesn’t mean their motivations are pure, or that their advice is good! But there’s some sort of guiding force, and that’s usually what leads the hero to finally accept the call after their refusal. If you want to be cliché, the mentor is an old man who helps the hero and then heroically sacrifices himself at this point so that the hero can survive and keep fighting. But there are plenty of variations.

Stage 5: Crossing the Threshold

We’re in the new world now! This stage is either the process of crossing (as that’s sometimes complicated) or adapting to the new world. Again, this does not necessarily mean a literal world aka setting. It can be a poor farmer (ordinary world) who discovers that they’re actually destined to save the kingdom (call to action)! They try to ignore it, but then enemies track them down, and they’re no longer safe (refusal of the call). Finally, after guidance from the wise village elder (mentor helper), they’ve accepted their destiny and are ready to go. That acceptance indicates that they’ve crossed the threshold into a new world, one in which they’re the chosen one. Even though the setting is the same, their perception of it has irrevocably altered.

Stage 6: Tests, Allies, and Enemies

This stage actually takes up a lot of space in the story, as it’s where a lot of the rising action happens. In the 4 Act Structure, this is Act 2. It ends when the hero is finally ready to face the main enemy.

Stage 7: Approach

This stage includes everything from when the hero begins their approach to the final battle up until the final battle itself. It’s important to note that there can be false approaches! This is very common. Think of Super Mario Bros–the princess is in another castle!

Stage 8: Final Battle

The time has finally come! This isn’t necessarily a physical battle, though it often is, especially if this is a video game or action movie. It’s just the big confrontation between the hero and the main antagonist, whatever that antagonist is.

Stage 9: Reward

Yay! The hero succeeds! They definitely deserve something, right? Well, yes and no. In some stories, the hero gets exactly what they wanted. In others, they realize that they actually wanted something else. Sometimes they get nothing but knowledge or understanding, and sometimes they get peace and nothing else. In slow burn romances, this is when they finally get together for that long-awaited kiss.

Stage 10: Road Back

This is sometimes a brief stage, and it just has the hero returning home in some way. This is either a literal return home with a literal road, or it can just be a return to a status quo.

Stage 11: Atonement

Now hold on a second, did you think it was really that easy? This stage gets skipped so often, and it’s so important. Definitely my favorite stage, and this is why the Hero’s Journey is my favorite. The hero has defeated the enemy and returned home… But what’s this? Home itself is under attack! The hero now has to use their new knowledge in the old world to save something of the status quo.

The best example of how important this stage is comes from Return of the King in movie form versus book form. Warning: spoilers for both. In the movie, Frodo destroys the ring (final battle), everyone celebrates (reward), and the hobbits return to the Shire (road back). Then, they live happily until Frodo leaves with Bilbo and the elves for Valinor. Good, right? Well, okay, but it could be even better!

In the book, when the hobbits return to the Shire, they find absolute carnage. Saruman has brought orcs to enslave the hobbits, and Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin arrive to destruction. They’re on their own with no humans, elves, or dwarves to help them. Using only their own new knowledge and skills, they defeat Saruman and restore the Shire to what it should be. Now they truly are heroes! When Frodo leaves for Valinor, he leaves his friends with the knowledge that they can handle any challenge that might come. It’s a far more satisfying ending, and that’s one example of how including this stage can make the difference between a good ending and a great ending.

Stage 12: Return

Now that the final enemy is gone, the hero settles into the new status quo, whatever that is. The dramatic question has been answered, loose ends are tied up, etc. Ah, the sweet, sweet taste of another story complete!

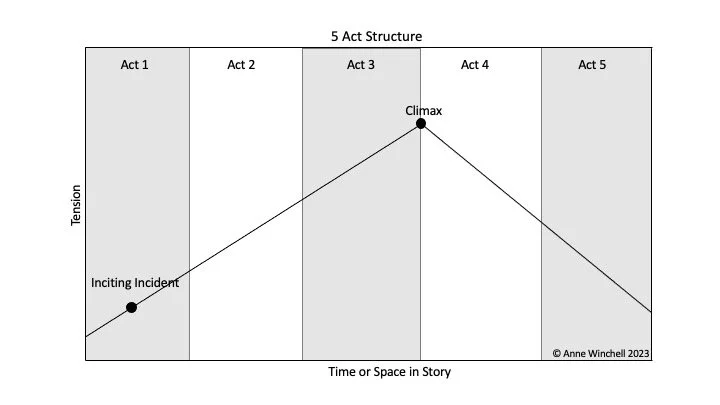

The Partial Exception: The 5 Act Structure

Some of you clever readers may have noticed that all of these structures are neatly divisible by three, convenient for different versions of the 3 Act Structure. However, you drama nerds may be screaming about the structure I haven’t addressed yet, the 5 Act Structure! (No offense meant by nerd, as I fit into this category as well!) While this one doesn’t track as beautifully on our graph, it still follows the 3 Act Structure. This format is common in plays and film, and made famous by Shakespeare. That’s why the drama fans and actors among you will pick up on it first! It’s also known as Freytag’s Triangle, by the way, and is his way of analyzing Shakespeare. Look at that lovely triangle in the graph illustrating the acts! I don’t use this structure myself, but it’s a great way of organizing things. The main drawback with this structure is that the climax happens a lot earlier in the narrative, and some authors (like me) prefer to wait longer.

Act 1: Exposition

Yada yada with openings. This is basically Act 1 of the 3 Act Structure. Introduce character and world, begin conflict with an inciting incident, establish the dramatic question.

Act 2: Rising Action

Similar to Act 2 of the 3 Act Structure, this includes (obviously) rising action! The tension grows. Characters try to accomplish their goals and fail (or temporarily succeed).

Act 3: Climax

While this seems like it would be the final battle (or equivalent), it’s more akin to the midpoint, since it’s when things begin to change. It’s a turning point, and also serves as the highest point of tension in the story.

Act 4: Falling Action

As the name suggests, the action begins to fall, but it’s important that there’s lingering tension as to how things will turn out. The dramatic question hasn’t been answered!

Act 5: Resolution

Here, everything wraps up as with previous structures. The dramatic question is answered! When analyzing Shakespeare’s tragedies, Freytag calls this “the catastrophe” because this is when everyone dies. But hey, yours can be a little cheerier, right?

Non-Western Literature

So, most people reading this… ugh, this is so itchy… MOAR TEA! I don’t know why the tea is making me so dizzy… Maybe there’s an explanation in the post on the disease. Actually, let me look at it, just a second. … … Wait, the tea is a type of poison?! Gosh, y’all had better read up on this disease!

(Vivian: Anne… is this gonna turn pandemic now?)

Well… 😅 Let’s hope not! I don’t think another pandemic would go over well right now! But I can get through this, especially as it’s about to get interesting. The majority of people reading this blog post will be most familiar with the Western tradition of writing, as most books are written this way, but let’s really look at that. You read the above sections and nodded, thinking it made perfect sense. As we’ve seen, Western culture prizes causality and emphasizes a beginning, middle, and end, with conflict being the driving force. This reflects the culture outside of writing, since the history of the West focuses on constant advancement and prizes overcoming adversity. However, this isn’t true around the world.

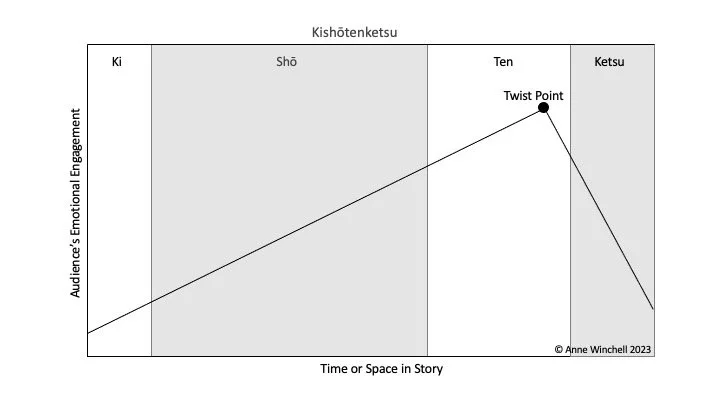

Kishōtenketsu

This popular East Asian form known as “stories without conflict” started in China, where it’s called qǐ chéng zhuǎn hé (起承轉合). Next, it moved to Korea, called gi seung jeon gyeol (기승전). From there, it went to Japan, where it’s called kishōtengō (起承転合). The English term (kishōtenketsu) comes from the Japanese version, though it’s slightly different. There’s your history lesson of the day!

Traditionally, this structure is used for poems, but it’s been adapted to everything from movies to video games. You can even use it in arguments, dissertations, and music! The key defining feature is the lack of conflict as a major factor in the story. All versions follow loosely the same structure, with some slight variation due to specific national and cultural norms. I’ll just be going over the basics and common elements of kishōtenketsu. (Vivian: Emoji name is 🔑📺🔟❓as I see it)

When looking at the graph for this structure, you’ll see that at first it looks quite similar. But wait! No, seriously, wait. This is super important! Look at the y-axis! The story arc is based on rising levels of the audience’s emotional engagement, not tension. Conflict is not the driving force of these stories. It’s all about the audience, their emotions, and how engaged they are. As with all previous graphs, this shouldn’t actually be a straight line, but should have waves of increased emotional engagement that loosely follow the linear increase and decrease.

Introduction(ki 🔑)

Where does any story begin? Why, at the beginning, of course! And what do you need to know to get started? Well, the same basics we saw in all of the Western structures, with one key difference I’ll get to in a second. First, you want to know the characters. Who are they? What are they like? What motivates them? What are their relationships? You also want to know the world, including the time period (which is often very relevant in older forms). World and character are always entwined, since we learn about the world through our characters. What are the rules of this world? How does everything interact? Sometimes we may even get into the driving force or reasoning for the story–why does it exist in the first place?

At first glance, this seems a lot like Act 1 from the 3 Act Structure, doesn’t it? WRONG. Act 1 sets up the status quo, then introduces an inciting incident that brings conflict into the story and sets everything in motion. We don’t have that here! Ki is all about introductions without a call to action or conflict.

Now, Ki is a fairly brief section, so you’re not going to go into too much detail here. This section is all about introducing the basic elements that will carry through the story and initiating the audience so they have an emotional link to the characters and world. After all, rather than relying on tension to push the plot forward as we get in Western narratives, everything here is driven by the audience’s emotional engagement. So in this brief opening, you’ve really got to hook them!

Development (shō 📺)

Shō is where we’re starting to take off! Things are happening! But what, exactly, is happening? Sometimes it’s a development in the world or in the situation, sometimes within the character themselves. The most important thing to remember, though, is that this is about rising audience engagement! Pull on those heartstrings! Make your audience feel for your story! Give them ups and downs while slowly raising the emotional intensity! However, you don’t want to spiral out of control… yet. Right now, you just want to capture your audience’s emotions and thoroughly engage them. After all, if they don’t care what’s happening, why will they keep participating in the story?

Twist (ten 🔟)

What’s this? A twist? Gasp! How can that possibly happen? Everything is starting to come to a head as a reversal or unexpected turn upsets the character or world. However, this isn’t your classic Western style conflict where the fate of the world is decided in one final brawl! No, this is more focused on emotions, relationships, and how characters relate to their own situations.

In Ten, your audience should be on the edge of their seats, fully engaged with what’s going on. Their emotions should be at a peak as they really feel for the story you’ve created. The sudden shift in your character, their situation, or the world overall should have the audience off-balance and waiting to see how everything resolves. This is the height of emotional engagement, so make that twist something that catches the audience’s attention and makes a true reversal.

Conclusion (ketsu ❓)

The end is nigh! Things have happened, the twist has been resolved, and now life is returning to normal. The audience’s emotional engagement slowly sinks as the characters fade back into the world. Maybe they find a new state of inner peace. Maybe their situation in life has improved. Maybe everyone is able to return home, or find a new home. Of course, it doesn’t have to be happy! There are so many ways to do this. Older forms tended to impart knowledge and lessons during Ketsu, and if you do something similar, make sure that information has been passed on to the audience before you tie up your loose ends. Alas, all things must end, and with that, we bid farewell to our East Asian story without conflict.

And in a way, we had our own kishōtenketsu here.

Should I Be Worrying About This While Writing?

Well, that depends! There are three basic ways of using narrative structure when writing. All have their benefits, but it really depends on your style of writing and what your story needs are.

Prewriting

For people who like to plan out their books in advance (known as Plotters), using one of these structures is a great starting point. Writing a Western story? Start by figuring out your dramatic question so that you have some direction in your story. Then, you can look at your chosen structure to figure out what needs to go where and how to build your story. Any of these structures work for this depending on what you want, and how much support you need. If you just want broad strokes guidance, go with the basic 3 Act Structure. Want to really dive in? The Hero’s Journey is quite detailed and can guide you towards a better story. However! Don’t let this dictate your story too much! Leave some room for flexibility and uniqueness. These structures outline the ways that tension should naturally rise and fall but shouldn’t dictate exact events. But if you are stuck and need to figure out where your story should go next, it can help.

Circumwriting

(Circum from around)

Speaking of using dramatic structures when you’re stuck, that’s often what happens for Plantsers (who are a cross between Plotters and Pantsers–what are those? Be patient! I describe them in the next section). Plantsers have a loose outline of what they want, but leave most of it to inspiration. I fall into this category most of the time!

When you use dramatic structure for circumwriting, you’re writing around the structure (hence the name! Get it?). For example, I tend to write for a while, then look back to see how my story has progressed and if I’m following my loose outline (and mine are extremely loose). You can also look ahead. Sometimes, when I start writing a scene, I’ll look at what I need the scene to accomplish. This is typical plantser behavior–work on a scene-by-scene basis. If you match it with a narrative structure, it works really well!

Postwriting

If you’re a Pantser, meaning you write by the seat of your pants (see, I defined it!), then you’re not thinking about structure when you’re getting through that first draft. You just want to write! I’ve done this on occasion. If that’s also you, then just write your heart out, because as any experienced writer knows, writing isn’t over when you finish the manuscript. That’s where revision begins! And that’s when you can start figuring out your structure.

No matter what type of writer you are, whether Plotter, Plantser, or Pantser, you’ll eventually get to revisions. When you look back over your draft, you usually have some changes in mind already, or things that you know you want to adjust. It helps, though, to make a brief outline of chapters or scenes so that you can map them out against a narrative structure. This ensures that your story is cohesive, consistent, and builds dramatic tension successfully. Just like with prewriting, you can choose any of these structures. They all have their benefits, so just choose the one that fits with your goals the best.

If you haven’t already, make sure you identify the dramatic question. After that, just ensure that the story builds appropriately and the dramatic question is answered in some way.

Summa Summarum

Dramatic structure is the key feature of a good story, and it’s what keeps your audience engaged. Without it, you’d just get the ramblings of a five-year-old, and no one likes that!

You can approach it in any way, but make sure to eventually address it. Revision is a great place. If there’s a scene that doesn’t seem to work or a plot line that feels out of place or unsatisfying, look at where it fits in the overall narrative arc and how it relates to the major dramatic question and adjust accordingly. It’s great for nudging things in order and making sure everything makes sense and works together to create a strong narrative.

No matter what structure you choose, make sure it fits the story you want to tell, and above all else, have fun with it! You need to be engaged too, so challenge yourself and enjoy.

(Vivian: If you found the llama emoji, comment where it was! Anne, why are you doing the tea!?)

Well, that’s what the post on Lightpox says… Wait a second… Shoot! I stopped reading at the traditional cures! We’re in modern times, and there’s a modern cure! Why am I doing the medieval cure?! Vivian, I blame you for not pointing this out earlier! I’ve now put in an order for the antibodies, and my shots should arrive soon. I’m not looking forward to it though… This is all Vivian’s fault for sure!

Want to dive into a discussion about Stellima or the art of writing on Discord? We’d love to have you! And if you have any topics you struggle with or that you would like to suggest for a future blogpost, we’re open to suggestions!

Interested in supporting our work? Join our Patreon and become a part of Stellima as a citizen of Mjatreonn! Or would you like to give us some caffeine to fuel our writing? Consider buying us a coffee at Ko-fi! Every contribution inspires our creativity and keeps us going. Thank you for your support!

Copyright ©️ 2023 Anne Winchell. Original ideas belong to the respective authors. Generic concepts such as dramatic structure and the types of structure are copyrighted under Creative Commons with attribution, and any derivatives must also be Creative Commons. However, all language or exact phrasing are individually copyrighted by the respective authors. Contact them for information on usage and questions if uncertain what falls under Creative Commons. We’re almost always happy to give permission. Please contact the authors through this website’s contact page.

We at Stellima value human creativity but are exploring ways AI can be ethically used. Please read our policy on AI and know that every word in the blog is written and edited by humans or aliens.